A worldview is often described as the lenses through which we see the world and our place in it. But this metaphor, while somewhat helpful, implies a worldview is something external like glasses. The view put forth by Wilkens and Sanford (2009) is that a worldview is more internal – an orientation of the heart.

The authors describe individualism as a worldview that emphasizes that meaning in life is found in a person’s ability to think and make choices for his or herself especially without reference to any external relationships or authority. In Western Christianity individualism has had the unfortunate effect of portraying Christianity primarily a relationship between an individual and God, generally without enough emphasis on the believer’s relationship with a church family or identification with the larger faith tradition of the church.

You can hear it in phrases like “I make my own rules; my personal relationship with God; religion is a private thing” etc.

How did this arise and why is this admired? Wilkens and Sanford note that the era after World War II is marked by a decline in trust, loyalty and commitment to established institutions in society like government, the legal system, financial systems, large for-profit corporations, and religion (esp. the Christian Church).

The reason for this decline is generally attributed to perceptions of the increased inequality of wealth and the exploiting of privileges and people from these institutions.

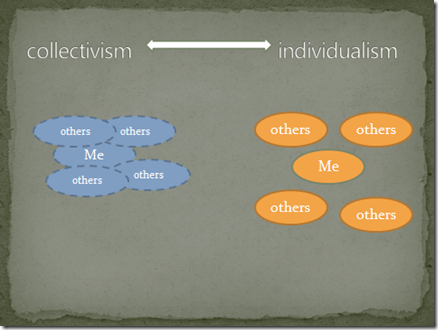

This tends to reflect a cultural worldview shift away from collectivism to individualism. Collectivism stands for a society in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups (extended family and more), which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect and provide for them in exchange for absolute loyalty. Whereas individualism stands for a society in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after themselves and their immediate family only. This continuum illustrates the contrast:

In church circles, individualism also describes the attitude of persons who refuse to agree with defined statements of belief or creeds, join themselves to a church family, or to submit to any external religious authority. Throughout history certain breakaway groups like this would call themselves freethinkers; others would profess to be Christian but refuse to adhere to any particular denomination or even a local church.

You can hear it in phrases like this: “You don’t need to go to church to be a Christian!; I have my own theology thank you!” etc.

Four times throughout Ephesians 1-2 Paul emphasizes that we are united in Jesus Christ (1:3, 11; 2:6-7). This united status comes not by performance or human choice, but by God’s grace. Those who believe are called “God’s masterpiece” (Eph. 2:10), but there is a different spirit at work in the hearts of those who refuse to obey God (Eph. 2:2).

Individualism emphasizes that meaning in life is found in a person’s ability to think and make choices for his or herself, without reference to any external relationships or authority. It is good to remember that God’s purposes are not primarily about me but rather about us. Wilkens and Sanford write: [Individualism represents how] influential a worldview can be once it becomes ingrained into the culture (our hearts) and how its power is magnified when we are no longer conscious of its pull on us. As a result, it is difficult for us to feel like we are valuable unless we can point to an impressive list of accomplishments. We sing “Jesus loves me” so loud it drowns out the proclamation “For God so loved the world.” The word freedom generates thoughts of what we want to be free from rather than what we are free for. The Christian faith is reduced to my faith [personal, private]. Commitments to others (preferring other; looking out for their interests) are potential obstacles to happiness rather than a source of happiness. God becomes a power source for the achievement of my goals, but I never get around to asking how my life lines up with God`s goals. (Hidden Worldviews, p. 41)